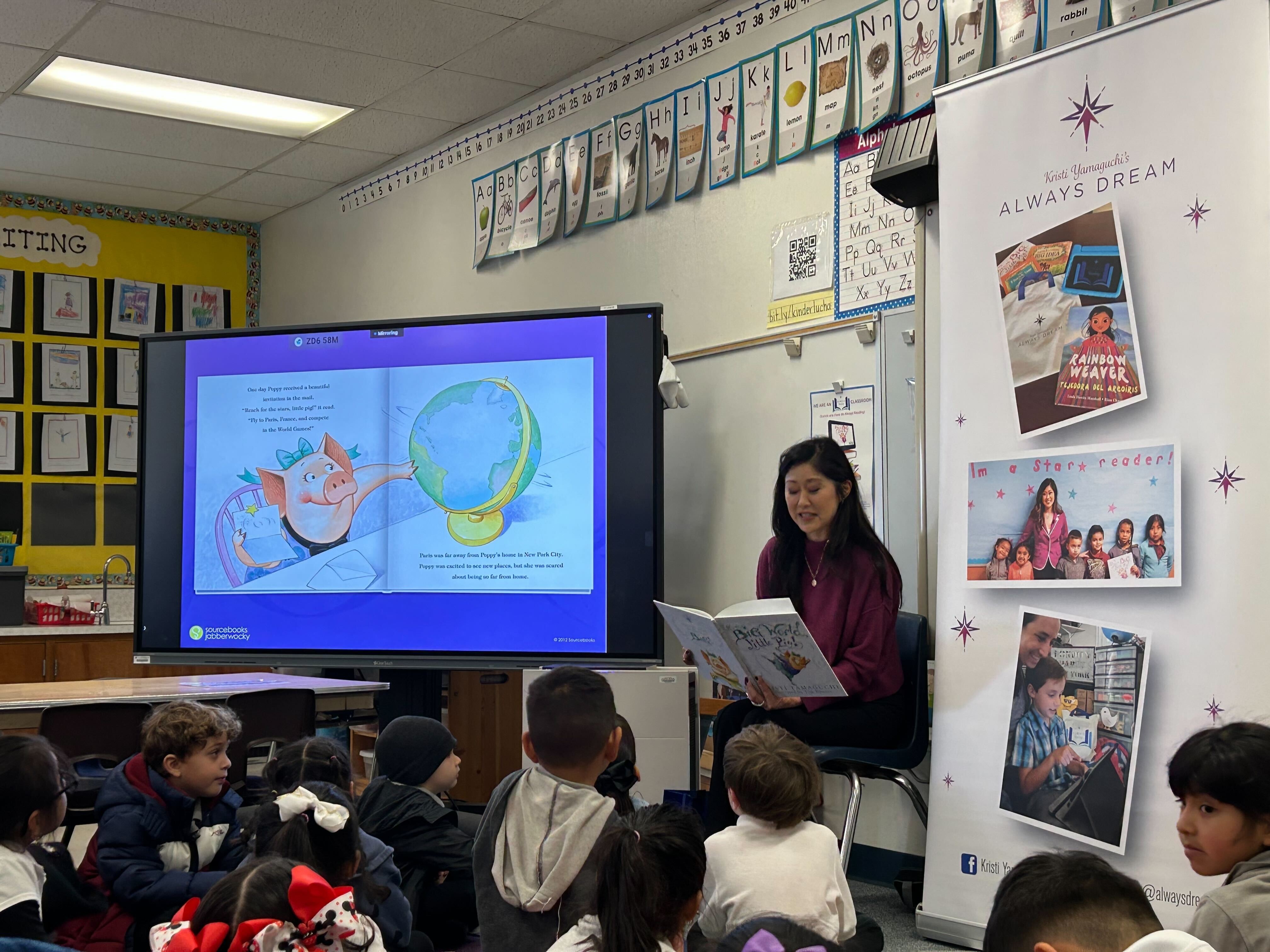

Above: Olympic champion Kristi Yamaguchi reads to a classroom of young pupils.

By Darci Miller

Kristi Yamaguchi’s parents were always community-minded. As she was growing up in Fremont, California, they encouraged her to give back, think about her community and do something beyond the ice.

In 1992, Yamaguchi won an Olympic gold medal. It was the pinnacle achievement in the sport, but what came after the Olympics was just as formative. She began touring with Stars On Ice, and the beneficiary for the tour was the Make-A-Wish Foundation, which grants wishes to children with critical illnesses.

The seeds of giving back had been planted, and now her eyes were opened.

“It was kind of my first time hands-on with a nonprofit and experiencing that, creating relationships with the families and the children,” Yamaguchi said. “It was just incredible and an amazing experience. So that inspired me to do something on my own.”

Four years later, Yamaguchi launched the Always Dream Foundation, which today is known as Kristi Yamaguchi’s Always Dream. For the first 15 years of its existence, Always Dream dabbled in different areas of philanthropy, always benefiting children. It fulfilled wishes of local children’s nonprofits, hosted skating shows, collaborated with summer camps and constructed the Always Dream Play Park in Fremont.

But in 2011, Yamaguchi published her first children’s book, Dream Big, Little Pig, and entered the world of children’s literacy for the first time.

“[The book] was inspired by being a mom and my two daughters, Kiera and Emma,” Yamaguchi said. “They were 4 and 6 around that time and at that learning-to-read age. And with that book launch, I was fortunate to be able to do a book tour and visit many schools, libraries, read to kids, just experience being in that world, and it was eye-opening.

“I think when we looked to go narrow and deep into one area to focus our efforts, we realized that, in order for kids to really have that opportunity to go for their dreams, they had to have a strong education. And where does that start? It starts with literacy. That’s the foundation. That’s what is going to set them up for success in school.”

Since then, Always Dream has worked with schools in Hawai’i and the San Francisco Bay Area, reaching kids ages 3 to 6 to provide at-home literacy tools. Always Dream supplies tablets with access to 40,000 children’s books, as well as several physical books each year, and a book coach to work with guardians on how to engage their children with reading at home.

In the 2024–25 school year, Always Dream partnered with 36 schools across Northern California and Hawaiʻi, helping more than 4,700 children and family members develop reading routines at home.

The impact Yamaguchi and Always Dream are having is real. Yamaguchi recalls a student named Amelio, who started the Always Dream program as a nonverbal pre-K student on a personalized education plan.

“His grandmother, who was essentially his primary caregiver, took advantage of all the resources and leveraged everything that our program was providing,” Yamaguchi said. “She read to him, they were diligent at reading, and about halfway through the year, he started asking questions. He was interested in the books they were reading and started asking questions about them. She kept it up, and by the end of the school year, his teachers got together and decided to take him off the personalized education plan and mainstream him into his regular kindergarten class.”

There are thousands of other students out there just like Amelio whose lives have been changed thanks to Always Dream. It’s a legacy for Yamaguchi that goes far beyond her achievements on the ice.

“It’s certainly something I’m proud of,” she said. “We’re in our 29th year as an established organization, so I’m proud of that. I’m grateful for the amazing team at Always Dream as well that has gotten us to where we are right now.”

But Yamaguchi hasn’t stopped at just childhood literacy. Never one to stray too far from her figure skating roots, she’s also served as a mentor for the new generation of skaters, notably 2014 Olympian Polina Edmunds and 2022 Olympic Team Event gold medalist Karen Chen.

Yamaguchi said she wouldn’t offer technical feedback, but she would give advice on how to handle pressure, navigate competitions and bounce back from failures.

“I had mentors like that, too, coming up,” Yamaguchi said. “Other skaters at the rink, and Brian Boitano was a mentor for me, even though it wasn’t like we would sit down and chat – just by leading by example, and I often got to train with him and watch how he trained and handled situations. I know what they’re going through or about to go through, and having been through it, I’m able to offer insight on how we handled certain situations or what helped me go through what they’re going through. If you can share that with the next generation, then why not? Paying it forward.”

Just as she wants every child equipped with the literacy skills to go after their dreams, Yamaguchi desires every skater to benefit from the community they’re in.

“I know there are many, many skaters who would love to share experiences with the younger generation, so don’t be shy to reach out,” she said. “Don’t be shy to ask. We’re here.”