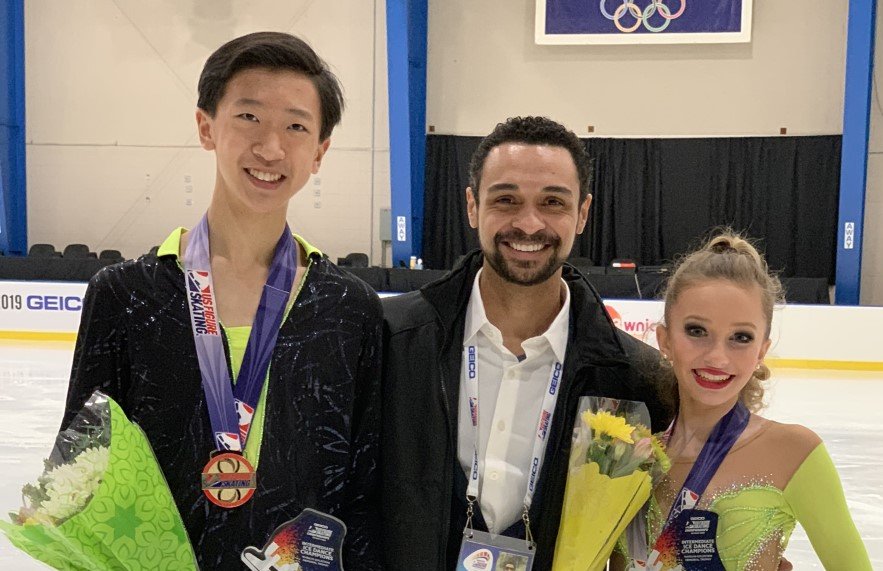

Above: Nathan Truesdell celebrates with his 2019 U.S. intermediate champion ice dance team of Nastia Efimova and Jonathan Zhao.

By Jillian L Martinez

In his more than 25 years on the ice, Nathan Truesdell has held a myriad of titles in figure skating.

To start, Truesdell is the founding director of the Ice Dance Academy of North Carolina (IDANC). However, unknown to many, he is also the highest-placing African American ice dancer at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships® and the first African American figure skating coach and choreographer to produce U.S. champions and Team USA athletes in ice dance. More so, his identity as an African American man and desire to incorporate different cultures into ice dance has been the impetus in his passion to make figure skating more inclusive.

“I started competing in freestyle [skating], but I was always inspired by my coaches [former internationally recognized ice dancers Yaroslava Nechaeva and Yuri Chesnichenko] because they were so stunning,” Truesdell said. “I saw videos of them and wanted to ice dance, too. I had never seen such beautiful movement on the ice.”

Historically, ice dance has drawn from ballroom dances, such as the waltz, which originated in European countries.

“Ballroom is very typical to be incorporated into an ice dancing program,” Truesdell said. “But I always felt like there was so much more to it.”

While Truesdell took off-ice dance lessons for many years as a competitive ice dancer, it wasn’t until he was a coach and choreographer that he began incorporating other dances, such as Afro-Latin dance, into his repertoire. The son of an African American Detroit musician, Truesdell has always valued music and the importance it plays in culture.

“As an adult learning more about my own family and cultural history, doing something like Afro-Latin dance showed me another side of Black culture,” Truesdell said. “[To be authentic], it was important to me to reach out to different cultures and communities to learn more.”

Such efforts to reach out and learn about Afro-Latin cultures and communities introduced Truesdell to his current dance instructor and mentor, Norberto “Betto” Herrera. Herrera has set the standard for Mambo dance companies in the Southeastern United States, according to Truesdell. Not only have Herrera’s skills helped Truesdell grow as a dancer, but Herrerra has also taught Truesdell more than steps and counts by sharing his knowledge and history of the Afro-Latin genre.

Using an educational approach to learning about Afro-Latin dance has brought cultural appreciation, rather than cultural appropriation, to bear on Truesdell’s art, craft and experience.

The difference between the two?

Cultural appropriation is defined as “the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture,” according to the Cambridge Dictionary. Cultural Appreciation, meanwhile, is rooted in the desire to understand another culture, not for personal gain.

“Off ice, I’ve also incorporated Afro-Latin dance into the training regime for my athletes to take the place of ballroom dance,” Truesdell said. “Similar to Afro-Latin dance, I have tried to take more of an appreciation-centered approach to introduce new styles and concepts to my athletes.”

Truesdell’s athletes all leave IDANC with the skill of cultural competency as they take Truesdell’s recommendations of uplifting and interacting with cultures not their own. More recently, ice dance has begun to incorporate selections of rhythms quite different from the historic waltz. For example, the ISU’s Ice Dance Technical Committee’s guidelines for the 2021–22 rhythm dance season requires at least two different rhythms from the following: street dance rhythms (such as hip-hop, disco, swing, krump, popping, funk, etc.), jazz, reggae (reggaeton) and blues.

According to Truesdell, the term “street dance rhythms” has had a negative connotation associated with it as comes from not being developed in a ballroom and referred to a style of dance different from the European norm.

As Truesdell’s athletes pick music to fit street dance rhythms, they are still encouraged to research the roots and culture of the music and involve community members in the design and construction of appropriate costumes along the way.

“This doesn’t always mean that if we have to use a street dance rhythm we are going to use a song by a minority artist, but it does mean I am going to challenge my athletes to learn about the ‘who, what, when, where, why’ in different genres and programs we use,” he said. “Then, we try to include people from the cultures every step of the way if we can.”

Outside his role in IDANC, Truesdell serves on numerous diversity and equity committees within U.S. Figure Skating, including the U.S. Center for Coaching Excellence, the Professional Skaters Association and the Diversify Ice Foundation.

“My love for the sport and my passion for my work has driven me to be involved and stay for so long,” Truesdell said. “My biggest motivation is for the future generation and to provide a healthier culture for anyone to flourish in.”

There still remain few Black and Brown skaters in the sport, Truesdell said, but as their numbers continue to grow, he hopes to provide inspiration, mentorship, and support for young skaters — resources he wishes were available to him when he was a competitor.

“The skating community isn’t perfect, but there are many who are available to support you [Black and Brown skaters],” Truesdell said. “If and when we are able to attract more people into the sport from underrepresented communities, I want to bring them into an environment that encourages them to see pathways and futures for themselves long-term and a community where they feel belongs to them just as much as it does for anyone else.”