By Robyn Clarke

The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March of 2020 forced the world to hit a curveball. Schools went virtual, restaurants closed their doors, and life, as it was known, came to a complete, abrupt halt.

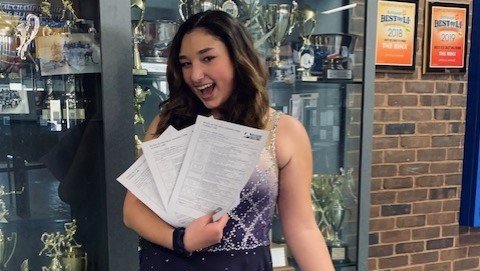

Most of society took time to adjust to a new normal, but for 13-year-old Gianna Intintoli, the onset of a then-undiagnosed illness two months before the pandemic started had already turned her world upside down.

“It felt like my body was on fire,” Intintoli said. “The whole entire time it felt like someone had just lit a match, and I was just burning all over the place.”

Up until January of 2020, Intintoli was a typical teenager. She attended school and spent much of her free time on the ice as a member of The Skating Club of New York.

Intintoli first stepped into a rink at age 3 after the preschool she attended offered figure skating as an activity. She enjoyed the sensation of gliding around a rink and quickly realized that other sports did not give her the same sense of freedom.

At age 5, she transitioned to synchronized skating. The move came after her family watched synchronized skating at the rink one afternoon and thought it was something Intintoli might be interested in.

Switching disciplines, though, was not easy.

“It was definitely a little bit different because it was a lot more practices and a lot more time on the ice,” she said. “But it was really fun because I was able to be with my friends.”

Little did she know how much she would come to lean on the synchronized skating community.

In January of last year, Intintoli was one of thousands of Americans to receive a flu shot. A few days after being inoculated, she developed a wide array of symptoms, indicating that something was wrong. Both her spleen and liver were enlarged, and she endured intense nerve pain that began in her legs and traveled to her head.

Eventually, it robbed her of the ability to walk and forced her to step away from skating.

“It was definitely hard,” Intintoli said. “Especially since we didn’t know if I’d ever be able to skate again. But my friends supported me and they always made sure I was OK.”

In one month, after trips to four hospitals and various doctors’ appointments, Intintoli was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome. GBS is a rare neurological disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks part of its peripheral nervous system, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The Centers for Disease Control reports that between 3,000 and 6,000 people are diagnosed with the disorder each year.

For Intintoli, the diagnosis brought relief. Now she could focus on her goal of learning to walk again.

The process was long, difficult and, at times, painful. Afternoon physical therapy sessions were a drastic shift from after-school skating practices. The arduous nature of her rehabilitation made the day she walked again all the more monumental.

It was in May, four months after Intintoli and her family had first heard the acronym GBS. She was in her living room, partaking in a virtual physical therapy session. With her mom as a witness and her therapist watching via the computer, Intintoli took her first steps.

“I remember just being really concentrated and really nervous. ... Seeing that I could walk for maybe three minutes one day and then four minutes the next day and then five minutes a day after that — it was exciting for me,” she said.

Intintoli did more than just learn how to walk again. A few months later, she got back out on the ice.

“[Figure skating] has definitely made me a better person,” she said. “It’s made me stronger [and] it’s made me realize I can be grateful for more things.”

Intitinoli recently detailed her Get Up story on the Voices From The Ice podcast. Learn more and listen here.